Mobile Tablets Drive New Era of Diagnostic Imaging “On the Go”

Stroll down the corridors of any hospital, and you’ll see dozens of physicians tapping away on their smart phones and tablet computers — because diagnostic imaging is not just for the radiology department any more. As the screen quality on these devices has improved, they have rapidly proliferated in doctors’ offices, the ER, patient rooms and everywhere in between as a potentially viable option for viewing patients’ medical images. After all, the pixels on today’s cell phones and mobile tablets are numerous and small enough to feed your eyes as much as they can see, and are sufficiently bright to be seen in most lighting conditions. But are they truly appropriate for use as a convenient — and most of all accurate — portable diagnostic imaging tool around the hospital?

Stroll down the corridors of any hospital, and you’ll see dozens of physicians tapping away on their smart phones and tablet computers — because diagnostic imaging is not just for the radiology department any more. As the screen quality on these devices has improved, they have rapidly proliferated in doctors’ offices, the ER, patient rooms and everywhere in between as a potentially viable option for viewing patients’ medical images. After all, the pixels on today’s cell phones and mobile tablets are numerous and small enough to feed your eyes as much as they can see, and are sufficiently bright to be seen in most lighting conditions. But are they truly appropriate for use as a convenient — and most of all accurate — portable diagnostic imaging tool around the hospital?

Extreme Accuracy is a Must

Developed as a consumer device, today’s mobile computers were not created to handle the resolution requirements of diagnostic imaging applications. The key limitation is that electronic tablets lack the necessary internal or external sensors necessary to achieve continuous, accurate DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) calibration, which is a standard in the field of medical informatics for exchanging digital information between medical imaging equipment (such as radiological imaging) and other systems, ensuring interoperability. In the healthcare setting, any mobile device must be DICOM-compliant, i.e., maintain image quality similar to a high-resolution radiology display in order to be used for diagnostic image review.

The good news for today’s increasingly busy and mobile physicians is that, if a screen can be properly calibrated, radiologists can diagnose images from most modalities like CT, MR, Ultrasound, including CR & DR. So far, these are the types of exams that have been cleared by the FDA for diagnostic reading on a mobile tablet when proper quality measures are in place.

The good news for today’s increasingly busy and mobile physicians is that, if a screen can be properly calibrated, radiologists can diagnose images from most modalities like CT, MR, Ultrasound, including CR & DR. So far, these are the types of exams that have been cleared by the FDA for diagnostic reading on a mobile tablet when proper quality measures are in place.

Tap Your Way to Precise Image Quality

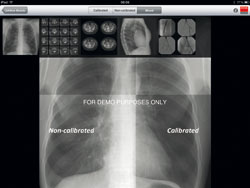

Fortunately, there are several options available that allow physicians to accurately calibrate their mobile tablet baseds on the use of a “tap test.” This visual calibration process ensures DICOM performance based on a user’s eyesight level and dynamic contrast based on the ambient light conditions. A third-party software tool can be integrated into any authorized mobile viewer application that has obtained all required registrations and certifications as specified by the FDA. Once properly calibrated, the mobile tablet can display images with excellent clarity and precision for modalities currently deemed acceptable by the FDA.

Ketan Thanki, Barco’s market development manager for healthcare in North America, explains: “There are numerous conditions under which a DICOM-calibrated tablet can be a safe, convenient alternative to a high resolution medical display: in emergency situations when a diagnostic display isn’t available, when a primary diagnosis has already been made using a full-size display, for consulting with other clinicians and in patient consultations.”

Form Follows Function

It stands to reason, that one should consider the real estate of the image before determining which imaging platform is best. For example, you wouldn’t use a screen the size of your wristwatch to navigate a path across the United States. By the same token, it’s difficult to properly evaluate an entire radiograph of the chest on a typical smart phone screen. That’s because no matter how many pixels are crammed onto the display, or how much zooming and panning you do, it’s nearly impossible to accurately interpret the image with such a limited viewport. So, while it may be possible to accurately read a large-matrix image on a tablet computer, no radiologist would desire to read 100 chest x-rays on such a small device. It’s just too cumbersome, time-consuming and simply ill-advised, especially when more appropriate alternatives are available. Without question, the image size/area is the driving factor in determining the ideal size of the medical imaging device.

Radiography also requires much higher luminance than possible with mobile devices; for primary diagnosis, no less than 350 cd/m2 should be used, and ideally 400 cd/m2. However, the luminance of most smart phones and tablets is perfectly acceptable in cases where a primary care doctor is reviewing findings made by a radiologist using a full-size display. For smaller size modalities like CT and MRI, most smart phone screens are typically up to the task as long as luminance is around 200 cd/m2. Naturally, the larger nine-inch tablet screens are even better suited for these viewing these images. The FDA has cleared the use of some mobile device software for small matrix images (non-radiography) only when a full workstation is unavailable.

Pixels and Image Quality — A Paradox

With most consumer displays, there is a direct relationship between pixels, screen resolution and perceived image quality. However, when it comes to medical imaging, pixels don’t tell the whole story. The number of pixels alone is insufficient to describe the resolution characteristics of a display (a fact which the American College of Radiology has addressed in its recent guidelines). Here’s why: The size of the pixels relative to the distance you hold the device away from your eyes is really what determines the quality of the image. The closer you hold it, the smaller the pixels should be to maximize what you can see. The larger the screen, the further away one tends to hold it, and therefore the larger the pixels can be.

In the Apple “retinal” display, the pixels are just below the threshold of what your eye can discriminate (so, theoretically, there’s no point in making them any smaller). So, while every display has a number of pixels you can count, that number alone is just one factor.

The general consensus among clinicians and governing bodies alike is that tablet computers are ideal for reviewing clinical images, such as during rounds and by residents and attendings as a portable viewer — but only for images upon which primary diagnosis has already been performed.

“They can and should replace the clipboard,” comments David Hirschorn, MD, director of radiology informatics, Staten Island University Hospital and researcher in radiology informatics, Massachusetts General Hospital. “A radiologist could perform primary diagnosis on a mobile device if it is properly calibrated, and only if he thoroughly examines the image via extensive zooming and panning to view enough of the original pixels. However, I would urge caution in cases where residents are making primary diagnoses themselves — such as in ICUs and other tertiary care settings. Extreme care should be exercised to use proper displays for those purposes lest they improperly treat a patient due to use of a substandard or uncalibrated display.”

What the Future Holds

As mobile devices evolve to process data faster, use less power (resulting in longer battery life), operate more intuitively — and as wireless network coverage expands — they will become even more ubiquitous in the healthcare environment. But further improvements to ensure DICOM compliance, as well as tracking and documenting image information, are also needed to make them a viable alternative to traditional medical displays. Once this happens, there will be no stopping the widespread adoption of mobile devices in diagnostic imaging in and around the hospital.