An Analysis of Crestron’s ‘Town Hall’ Sessions: Addressing the Supply Chain

It is no secret to the AV world that most companies have dealt with incredible supply chain issues in the past 18 months. We hear horror stories of companies changing ship dates from weeks, to months to even years. It is not uncommon today to hear of 18 -24-month ship dates. For some reason, much of the vitriol about this has been aimed at Crestron. This may be because the company is the elephant in the room of any AV discussion, or it may be because its communication with its clients was not clear. Either way, this blog is not intended to judge what may or may not be past failures or miscommunications. It is intended to react to the recent town hall events the company has been putting on. I was invited to a town hall session for higher ed clients specifically, and I know Crestron has also held some for other verticals.

I think it is worth writing about because it truly helped remind me of the ridiculously strange place we are still in as a cause of the pandemic. I am someone who has spent time reading about the chip shortage, the logistical issues plaguing shipping, etc., and yet I still learned quite a bit during the session I attended. Apologies if I got a detail wrong, and if so, I hope someone corrects me. This is not intended to be a complete recap of the panel, but rather what I learned from it.

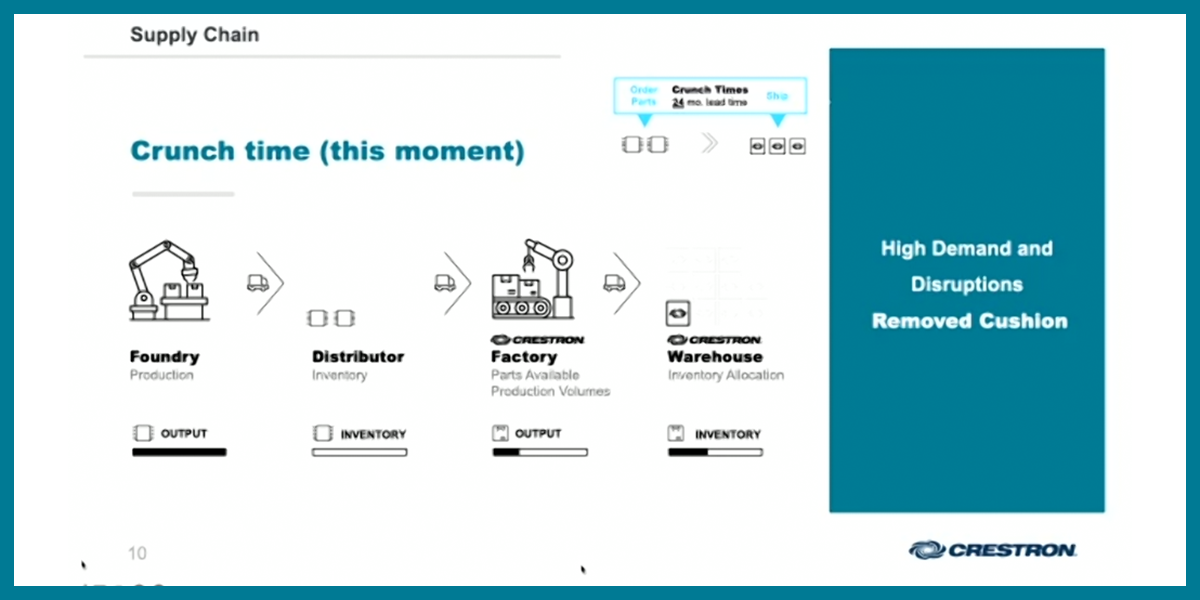

On the panel from Crestron were Dan Brady (COO) and Dan Feldstein (CEO). They started the discussion with a bit of history on how Crestron’s supply chain works. As we all know, the vast majority of chips are manufactured in China. From there, they are sold to three major distributors. For every product in the world that uses these chips, they have to go through these distributors. We also know that during the height of the pandemic the manufacturing of these completely stopped. What I never knew was that a company like Crestron would typically have a purchasing lead time for these supplies of 12 months before March 2020. Its supply chain managers would work with these lead times and plan out what they believed the demand would be. This indicates that even before the shutdowns, these plants were working at full capacity and already limited. Today, Crestron (and presumably other vendors) are having to deal with a 24-month lead time. Yes, they have to predict product demand two years in advance and make a financial commitment to that prediction. In addition to this insane lead time is the unpredictable nature of this market, and the pandemic itself. I learned that it is not unusual for a commitment to be made to Crestron for chips, and at some later date for that commitment to be reversed (“oops, sorry you’re not getting that order like we promised”). For several months at the start of 2022, much of China went through another full shutdown, closing all the manufacturing again, causing more instability and delayed or canceled orders, for example.

Another thing I learned is that a device like a DM-NVX has about 2,564 parts in it, most of them “jelly bean parts” as Dan Brady likes to call them. These parts can be sourced from over 240 different vendors. These parts would typically cost from less than a cent to a few cents. Today, when they are able to source the parts they can cost as much as 30 to 40 dollars. Feldstein and Brady indicated that this is actually their biggest problem at the moment. The “smart” chips are available and sitting on circuit boards waiting for the jelly beans. But if you are missing a single jelly bean, the product does not work.

Brady and Feldstein also addressed the question, “why do your competitors seem not to have this problem?” They did not answer the question, because they could not. They don’t know what their competitors’ demands or supply levels are, so how can they know if others are having similar issues? Anecdotally, I hear that others are having the same problems. The manufacturer that is shipping out in a couple of weeks is very hard to find. To simply pile on more pain, the panelists told us that they have experienced a large increase in demand over the past nine months. In fact, demand exceeds other years leading up to the pandemic. Couple a huge demand surge, with a crashing supply line and you have a perfect storm.

One of the hardest parts to wrap our head around — and perhaps the struggle that Crestron itself has had — is how to communicate the unknown. When you rely on over 240 different vendors to get you parts in this environment, you are going to have instability. Yet, as consumers, we are not happy hearing “go ahead and order that, but I have no idea when you will get it.” So, all vendors try and give a date they can live up to, but then they have vendors cut commitments to them, and that changes their “promise” to the consumer. As Dan Brady pointed out “there are no magic bags of parts sitting around.”

I am fortunate enough to work in a vertical where my livelihood does not directly tie to supply being readily available. I (and others in the higher ed vertical) am lucky enough to be able to skip a year of upgrades as necessary, or to be able to focus on what we can get for rooms or buildings that are new. We are also able to use our previous strong relationships with our end users to explain the situation. We are lucky enough to have the ability to be patient, thoughtful and caring with the manufacturers in our industry. I was grateful that Crestron took the time to help all of us understand these issues, to give us resources to turn to if we need help in design, planning or even in explaining these problems to our bosses. In separate communications, several of my higher ed colleagues even indicated that Crestron had helped them integrate competitor parts into their systems when Crestron equipment was not available. That type of service and partnership is worth a second look.