5120 Is Not 4K and 4K Is Not UHD

After my last piece on 4K and UHD and the infrastructure challenges we face in order to implement it in its best form, I honestly thought I’d be done with the topic for a while. After all, the most recent piece I wrote on 4K before that was in May 2013, almost a year prior.

After my last piece on 4K and UHD and the infrastructure challenges we face in order to implement it in its best form, I honestly thought I’d be done with the topic for a while. After all, the most recent piece I wrote on 4K before that was in May 2013, almost a year prior.

Well I decided to make a joke about HDMI on Twitter and all of a sudden the snowball was in motion. That joke led to an exchange with Josh Srago on Twitter and then to a live debate on AV Shop Talk. The topics ranged form general 4K questions, to infrastructure issues, to the new HDMI spec. Specific to the 4K discussion was an exchange about the marketing confusion around 4K, UHD and 2160p. I assumed that at least the four of us left that conversation knowing the differences.

Today, I was mentioned in a tweet by AV Shop Talk regarding Samsung’s new $120,000 105″ curved display.

They quickly realized a couple minutes later that this wasn’t a 4K display but that the display would be 4K compatible in a pixel for pixel arrangement.

I don’t blame the guys at AV Shop Talk for their initial confusion; they’re extremely bright and well versed in AV. I blame the way that companies have marketed the technology. It’s been as clear as mud.

I couldn’t help but crack open my laptop on a Saturday night to try to put this to bed even in the face of my own insomnia, so here goes.

The only displays that are “4K” are 4096 pixels wide.

No more, no less. 3840×2160 is not 4K. 5120×2160 is not 4K.

3840x2160p is UHD-1. That’s what it is. That’s what we should call it because it’s important. We have to understand the nature of our displays in order to do our jobs correctly. It allows us to know what happens to our signals when they hit the display, and how to best create content to assure the best delivery.

We always get the best result when we can send a display content in the native resolution of the display. This eliminates any scaling of the image.

Secondarily, if we cannot deliver content in that native resolution, it’s best to deliver it in a way that it can be scaled more easily. This typically means working in round multiples of the native resolution. This is one of the reasons that broadcast decided to go with 3840×2160 or UHD-1 instead of the existing cinema format of 4K. Existing HD content in the 1920×1080 format scales easily into 3840×2160. Both the vertical and horizontal resolutions are doubled, creating four times the total pixels of the 1920×1080 signal. If you tried to scale a 1920 wide image to a 4096 wide display, the math gets a lot messier, and scaling becomes somewhat harder and makes the image look worse.

(Think about this: Even when the math is easy, the scaler in a UHD display is having to create 4 pixels for every one that it has data for in a 1920×1080 signal. There is more created data in the image than there is original content. That always decreases quality of the image itself, even if the resolution is higher.)

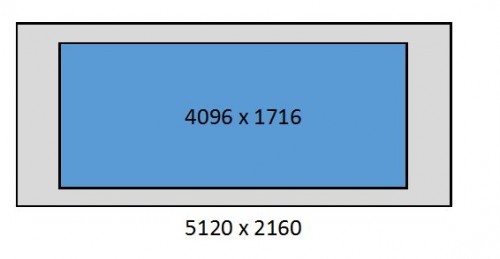

So why did Samsung pick the 5120×2160 form factor for their new monolith? (We won’t get into the curvature now but I questioned curved screens earlier this year as well.) The display is obviously created for CinemaScope content, which is wider than the standard 16:9 format we have on all the other UHD displays. Why would they create a format that uses a canvas LARGER than the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) created by the studio? This requires the image to be scaled and stretched to fit the display, or if you do a pixel for pixel match, leaves a black border all around the image. (See Below)

CinemaScope in a DCP is 4096×1716. Wouldn’t it have been smarter to make a display with that native resolution? I would argue that the answer is yes, IF the display was ONLY being used for 4096×1716 DCP content (content that I got Sony Pictures Home Entertainment to agree to sell to private individuals for home systems back in 2010, but that integrators felt they couldn’t sell so it died).

However, we know these displays will also be used for other content as well. Cable/satellite TV content will be 1920×1080 most likely, as will Blu-Ray content. Other cinema DCP content is 3996×2160 (1:85:1) — so scaling those images to a 4096×1716 canvas would cause the scaling issues referenced above. Again the math there is messy.

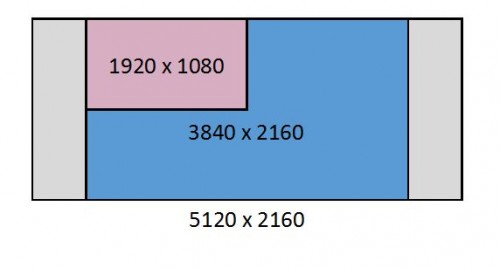

Samsung kept the vertical resolution at 2160, the same as the UHD standard, so that native UHD content would not need to be scaled down. That also means that the scaling can utilize round numbers for older 1080 signals. Both scenarios leave black bars left and right of the image, but fill the vertical resolution of the display fully. (See below).

Obviously that holds true for 3996×2160 (1.85:1) cinema DCP content as well.

And herein lies the irony. The very images that the aspect ratio of the display was designed to accommodate are the only images that the display will actually have to apply some rather complex scaling to in order to fill the screen completely and eliminate the black bars. This means the extra wide images the display is being sold to reproduce may most likely be the ones played back least accurately with the most artifacts.

At the end of the day, the vertical height of the $120,000 display is nearly the same as an 84″ diagonal 16:9 screen. It would be wise to reflect on what the majority of the content you consume is, and then decide whether you’d rather have black bars on your every day content to get a wider image on movie night, or whether you’d rather fill the screen on a daily basis and deal with the black bars when watching movies.

These are the type of conversations we should be having with clients when talking about 4k and UHD. Understanding the differences is the only way to help eliminate confusion and make those conversations valuable.

Have I jumped off the deep end here of AV Geekery? Let me know in the comments.