One Touch of Nature Makes the Whole World Kind

As a consultant who has spent a great amount of time over the last 10 years designing technology systems for performing and cultural arts facilities and as a professional in the very same industry for over 26 years, I am often struck at the unbelievable willingness and resolve of the people involved in these endeavors to seek out better ways of producing art. Most recently there has been a renewed and concentrated focus of making the arts sustainable with real opportunity to do so. Some of this comes from decades of experience in reducing, reusing and recycling out of pure financial necessity, while the rest comes from an understanding that this undertaking provides for a social, economic and environmental benefit to the arts, the communities they serve and the environment in which we live and operate. The current state of technology is such that real opportunities to play a major role in this exist for the first time in history. It is more than simply presenting opportunity for a “green” arts industry; it’s a smart arts undertaking that truly is sustainable in every sense of the word.

As a consultant who has spent a great amount of time over the last 10 years designing technology systems for performing and cultural arts facilities and as a professional in the very same industry for over 26 years, I am often struck at the unbelievable willingness and resolve of the people involved in these endeavors to seek out better ways of producing art. Most recently there has been a renewed and concentrated focus of making the arts sustainable with real opportunity to do so. Some of this comes from decades of experience in reducing, reusing and recycling out of pure financial necessity, while the rest comes from an understanding that this undertaking provides for a social, economic and environmental benefit to the arts, the communities they serve and the environment in which we live and operate. The current state of technology is such that real opportunities to play a major role in this exist for the first time in history. It is more than simply presenting opportunity for a “green” arts industry; it’s a smart arts undertaking that truly is sustainable in every sense of the word.

First and foremost, we need to truly define the word “sustainability” without all the green wash. Webster’s defines sustainable as “capable of being sustained; of, relating to, or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted permanently or damaged beyond repair.” It is the capacity to endure. However since the 1980s, sustainability has transformed the meaning of human sustainability on the planet into the concept of sustainable development. In 1987, the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

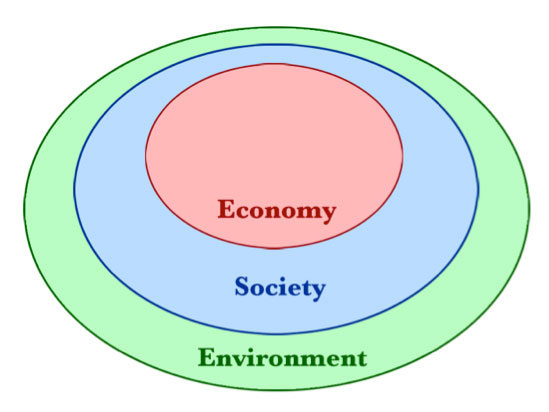

To achieve this, the 2005 World Summit of Social Development created what is now known as the “three pillars of sustainability” — Environmental, Social Equality and Economic. The three circles diagram below shows how these three pillars are not mutually exclusive but interdependent on each other and are quite often referred to as the triple bottom line.

Sustainable development is seen as an oxymoron by many since development in and of itself prescribes destruction and some degree of environmental degradation to be successful. From this vantage point, the economy is a subsystem of human society. Human society is a subsystem of the biosphere. So a gain in one sector is a loss in another. A true universal definition has had difficulty in coalescing because of the political nature of it needing to be scientific and factual. Who gets to decide what is scientific and factual is at the center of the debate. Just mention global warming to a politician and you will see what I am referring to. The simple lay definition then is improving the human experience while living within the limits of the ecological systems in which we call Earth. This explanation sets up limits and conjures up political calls to action set around common goals and values. In particular, this not only can refer to human sustainability, but also incorporates situations and contexts over vast scales of space and time from the local to the global balance of consumption and production. It implies structured and agreed upon decision making, innovation and resolution that minimizes impact and maintains balance among the three pillars to ensure the desired results for all environments now and in the future. This is evident in the below famous Venn diagram showing the confluence and interdependence of the three pillars.

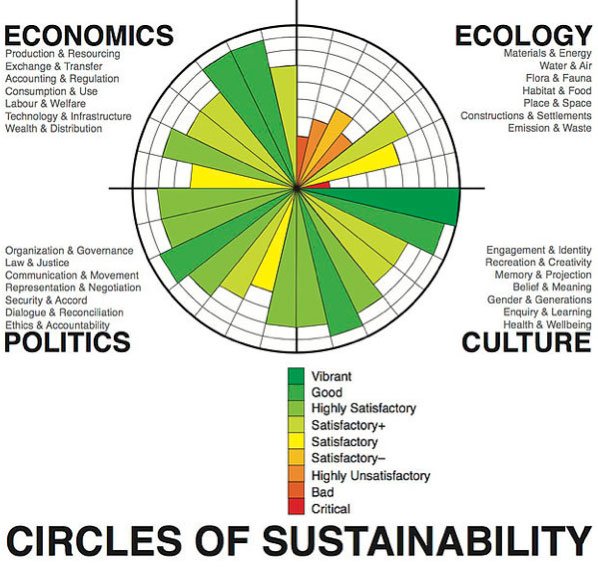

This is why many see sustainability as a purely “feel-good” mantra while to others it is a life or death concept. To add to the mix many have described sustainability as requiring that culture also be added to the model. Arts are significantly about culture and therefore have had some difficulty in fitting the three circle model efficiently. The emerging alternative known as the Circles of Sustainability looks at the economic side of the equation and asks why it is either central to the three-circle diagram or is located outside of the social as shown in the Venn diagram. The UN Global Impact Cities Programme uses this model (shown below) to further integrate real world challenges. What I find most interesting is that from a standpoint of the technology systems employed into the arts environments we design, this model represents a clear picture on the impact we can make with the systems we design and implement. I feel it also provides a clearer roadmap to the arts operators as to how to resolve sustainability from an operations standpoint.

So to head back to sustainability in the arts and how this all fits in, we have to look at how arts organizations function within the construct of the models. It is quite often apparent that from the social side of the equation, the arts ranks pretty high and has a clear track record of providing longevity to be sustainable. Let’s face it — the arts have been around for thousands of years and don’t appear to be going anywhere soon although it has been economically more challenging in the last few decades here in the U.S.

Arts, throughout history, have provided thought and direction, cultural enlightenment, education, entertainment and most importantly, a way to communicate with our contemporaries. The essence of art is a three-legged stool — one artist, one spectator, and one idea to communicate. At its simplest it is sustainable with no perceivable impact on the constructs of the model other than location. The arts can simply just be without fancy structures, lighting, sound, costumes or other amenities we have become accustomed to. This would easily be understood thousands of years ago to the first storytellers conveying their ideas to their peers under the sun or around the campfire. We, however, do not live in that world. We expect our arts to be in technologically rich environments with all the bells and whistles to capture our attention and imagination as it competes with other forms of entertainment. This does not make for a very sustainable practice from an economical sense or and environmental one as arts are inherently energy inefficient but from a social and cultural has proved vital. This is not to say the other areas are not impacted.

Modern arts organizations do have a significant outward impact on the economy in which they reside. They provide jobs within their venues and help to maintain the economic engine of surrounding businesses such as restaurants and retail. If they are successful, they may generate a profit or other financial endowments that allow them to maintain their contribution for generations to come. This is a huge boost to local economies and has been well documented by the Theater Communications Group, which provides many studies on the economic impact of arts facilities on communities. Where most fall short is in the impact and inefficiencies of their operations. Much of this is a result of tradition in the way art is produced but is often out of financial hardship as not-for-profits often struggle for operating capital. As a consultant, we often work with our clients to investigate their operations and see how efficiencies can be gained to better the financial burden of operating what generally is a substantially intensive and expensive venture. Generally easy targets can be in building systems such as HVAC and lighting (two usually large bills). It often extends into the environmental side of operations in that resources are used more efficiently then they save money. What has to be the driver is that a measurable benefit must be seen and felt by the company otherwise there will be a perceived failure on their part making it less likely that they continue with the strategy.

In the first part of this article, I want to examine the built environment. If an arts company has decided to make improvements or renovate a facility, we have the opportunity to work directly with them to better their operations as well as provide them with a better building. Most arts building owners are by now well aware of the U.S. Green Building Council and the LEED rating system or maybe even other rating systems that can help guide them towards a better facility with lower operating costs from a building operations perspective. The key is for us to help educate the clients on how their operations will be impacted by the decisions made during the design and construction of their project. This truly means that operations and the design and construction of a facility are not separate issues. They have to be dealt with together to achieve the maximum benefit. This includes not only building operations, but also production operations as well.

It surely would also benefit organizations from engaging with consultants to evaluate their operations — both from a facilities side and a production side — to see if there are changes that can be made to improve their operating costs. This may lead to a construction project or a technology refresh that was not necessarily planned but can have an overall impact on the triple bottom line. Here is where a good understanding of what the client can expect as a return on their investment is a benefit to you and the client. This is not exclusive to the arts but there are usually much larger technology systems in these venues that are driven by larger than normal energy demands and operating costs.

What you may be unaware of is just how informed an arts organization is on strategies to improve their process. There are now several organizations for the arts dedicated exclusively to sustainability, including the Broadway Green Alliance, The Center for Sustainable Practice in the Arts and Julie’s Bicycle to name a few. Other trade organizations such as InfoComm, USITT, ESTA and PLASA also have had many sustainability initiatives. Many festival and arts organizers are having competitions and are sharing ideas or producing demonstrations of sustainable arts practices. The Edinburgh Fringe Festival, for example, held a competition in 2012 for the most sustainable production that included the facility as well as the performance. Also, for instance, I took part in the first Sustainable Practice in the Arts summit this past summer in Minneapolis with many colleagues who are practitioners in a two-day summit discussing ways of being more sustainable within their arts organizations beyond just what the building can provide. They are informed and eager to work with you on the sharing of ideas and strategies. We need to embrace that, nurture it and find ways to lead the conversation.

When looking at the built environment, many of these are in facilities made during the great experimental architecture period of the ‘60s and ‘70s, many of which fail miserably when it comes to efficient building systems. Energy was cheap (at least until the Oil Embargo of the mid-1970s). Others are in older buildings usually made in the 1920-30s that are on historic registries. These buildings are expensive to renovate and even more expensive to maintain. Their mechanical and electrical systems are in dire need of upgrade and usually are not up to capacity of a modern production. The technology itself can be old and out of date and require extensive overhaul to bring to safe, current, working condition. Modern new facility construction is the best opportunity to create a demonstrable efficient environment that truly is sustainable for the arts organization. Our work as technology designers who should understand the ins and outs of operations within these facilities can be a key driver in how the final outcome shapes up.

For these projects to be successful, sustainability must be an identified and agreed upon goal as the single most important thing you can do for the arts organization. It simply must be understood that the majority of these projects are funded through donations from foundations, corporations and private citizens who are favorable to an arts institution. They must for that very reason be excellent stewards of the generosity of their patrons. This can differ very much from the corporate or other for-profit markets where the costs are born entirely by that entity. Many times the donating party will require a measure of a sustainability goal and we have seen more operations pro formas being tied to this as well. They simply do not want to donate money to an organization for a building that will not be sustainable in every sense of the word.

So having that defined and mutual goal will actually make it relatively easy to achieve. Understanding the trade-offs of providing sustainable solutions and the ROIs will go a long way to the success of the project. As an example, you could prove to a client that a digital audio retrofit can be ultimately more sustainable as it may require fewer conduits, wire and installation time, which may save them money on the labor and infrastructure during construction. This is even though the cost of the components may cost more than an analog system. Proving out efficiencies in the operation of a digital audio solution regarding set up time and strike from a production standpoint as well as inherent ease of use is also critical to acceptance by the owner/operator of the facility. They also may achieve a benefit of being able to reduce power consumption and heat load, as more often than not the digital systems have incorporated many levels of functionality that would typically take many pieces of equipment to achieve with an analog system. Doing this as an afterthought will ultimately result in a less efficient design and more costs to the owner.

As designers, it is our responsibility to understand lifecycle costs analysis by working with manufacturers to know where the product comes from and if there are end-of-life programs that they may offer. If they don’t have this information readily available, then a great alternative is to have an answer for the client as to what to do with gear when it does reach the end of its useful life. Also, make sure you understand the power demands, monitoring and control options and that the client is clear about these systems and how they benefit them from a usability standpoint and an operations/economic benefit. Without conveying this they may not have that perceived value and think it to be ineffective and a waste of resources and money.

As designers we also have to look, as I mentioned previously, in the operations side and work with the client to better their production operations. You may be surprised what they are already doing and that you may have opportunity to offer other ideas. For instance, in an arts organization’s facility, there has to be a way to separate materials for recycling especially in a producing house where shop space exists. Productions often have dual carbon footprints — once when they are built, and once when they are struck and the end of the production. Reuse of materials can be critical and has the potential to save time, money and the environment. This means that working with the rest of the design team and the owner to identify storage requirements for stored materials has got to be part of the plan for sustainability.

There is inherent value in stock costumes, platforms, flats, cables, loudspeakers, projectors, hardware, etc. but these do need to be stored within a reasonable distance to the stage. Simply moving these items to an offsite location may seem the best economical solution within a project’s budget, but you may just be moving costs to operations and ultimately creating an unsustainable model as there will be time necessary for travel to the site possibly with multiple trips — most likely using an inefficient vehicle such as a van or stake bed truck for delivery. Every effort should be made by the design team to incorporate adequate storage onsite to minimize impact on operations, which will beget a more sustainable activity.

We can offer now more efficient technology solutions now that are using less electricity, generate less heat, have more controllability, better standby power and take less physical space during the production or when in storage. We now have a multitude of power distribution systems that have true intelligence to them by manufacturers such as Furman, Middle Atlantic and Lyntec. Ultimately this will work to reduce the total power demand to the building and result in the need for less cooling capacity. Communicating this to the building design team and to the owner is critical to staying on the path of sustainability.

Daylighting (a fancy word for having widows) within the facility, particularly within the performance venue itself is a great way to help with the overall building sustainability goals but can wreak havoc on a production without excellent blackout capability, which requires shades of some sort and a control system. Who better to be part of that strategy that those of us who provide control for so many other things? But we need to have that conversation with the team.

And what about heating and cooling needs? Making sure the mechanical engineer on the project understands the true demands of a well-designed system can significantly reduce HVAC systems. Fan wall technology and variable fan drives (VFDs) provide a smarter solution that runs on demand rather than all the time. These strategies also reduce low frequency noise requiring smaller silencers, duct-work and a reduced footprint which means possible more storage space.

Alternative power generation (wind and solar) may now be economically feasible with a reduced power demand by smart performance systems tied into a well-integrated building management system. In older facilities that may have a steam generation system with waste heat, you may look for opportunities to co-op the system during non-peak hours to adjacent tenants. This could potentially create cash flow for other operations costs such as purchasing gear for productions.

End of life opportunities should also truly be vetted out with the design team and owner/operator. Having a plan as to what happens to the production systems after the show is over is critical to discuss with the owner as part of a comprehensive operations plan. Minimizing waste on the tail end and designing the production around what will happen after the show closes can be a great benefit to the organization reducing costs and potential landfill material. Having that storage is a great way to start. Possibly reselling or donating no longer needed equipment (in good working order of course), or finding e-cycling opportunities for no longer functioning electronics should also be part of the plan. Regularly scheduled equipment maintenance and actually having a plan to keep the place clean and organized will help to extend the life and service of technology for future productions.

This just scratches the surface on opportunities to work with facility owners and design teams for renovation projects or new construction. The second part of this will look at the traveling and temporary arts and what can be done to be more sustainable when you don’t have a home.

Raymond Kent is the Managing Principal of Sustainable Technologies Group, LLC specializing in technology systems for the performing and cultural arts, healthcare, Government, higher education, and corporate markets. He is a co-author of the STEP rating system and serves as the chair of the Technology Task Force for the STEP Foundation. Raymond received the 2012 InfoComm Sustainable Technology Award and is involved with the Center for Sustainable Practice in the Arts. Reach him at rkent@sustaintech-llc.com