Everything You Wanted to Know About the Chip Shortage (But Were Too Embarrassed to Ask)

It’s a scenario currently playing out at AV integrators all over the world. After a difficult year of pandemic-induced budget cuts, a client accepts a proposal for an install or upgrade. Paperwork gets signed. Purchase orders get cut. Product orders go out. And then … the waiting game begins. Phone calls are made. The waiting continues. More phone calls. More waiting. From the manufacturer to the distributor to the integrator, all anyone can do is wave their hands and say, “well, you know, chip shortage.”

So what’s going on, anyways?

All of those products that you’re waiting for contain semiconductors/microchips (heretofore referred to as “chips”), aka tiny circuits that provide processing power. The vast majority of these chips are made in China (as well as a few other countries in Asia) and then shipped around the world. Chips are used in a wide range of electronic products from motor vehicles to smartphones to (you guessed it) DSPs. If you were to crack open two products made by competing manufacturers, there’s a decent chance that you would see that some of the chips inside them are exactly the same. For those who spent the last two years rediscovering themselves in a cave in the mountains, you should know we have been enduring a global pandemic. Said pandemic disrupted entire supply chains. COVID-19 hit all of the places where chips are manufactured hard. This slowed down (and, in some cases, halted entirely) the production of chips.

Most of us remember 2020 as a year when we all binge-watched Netflix in an effort to stave off that feeling of impending doom. But, as you probably don’t remember, it was also a year where we came within inches of an all-out trade war with China. And mother nature tried to get us off her back with a series of extreme weather events. Neither of these helped us get our chips any faster.

Finally, the spending habits of a global population trapped inside and hosting Zoom happy hours set off a global restructuring of production lines. We weren’t buying new cars, but everyone and their grandmother was trying to get their hands on a Chromebook. Struggling companies reduced their orders. A booming technology industry vacuumed up all the extra chips in the system. Microchip manufacturers rebalanced their lines and then, as various industries recovered at different rates, pent-up demand created further production imbalances. A factory fire in Japan took down production.

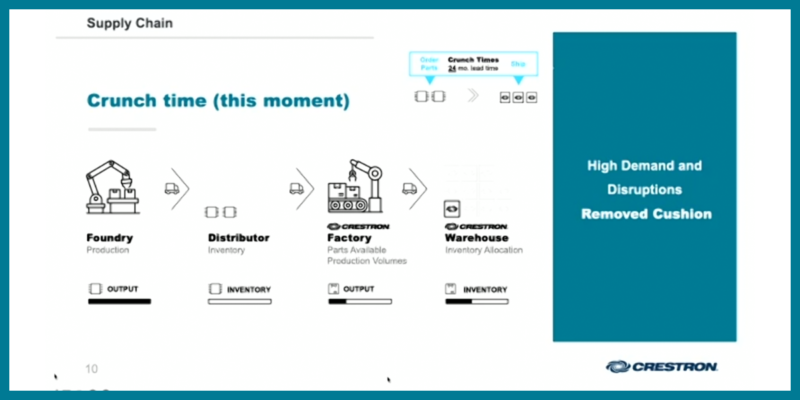

In many ways, the global supply chain fell victim to its own efficiency. Most companies use a “just in time” process when it comes to sourcing. When things are running smoothly, everything arrives just in time to be useful (which is more cost-efficient). But, when things aren’t running smoothly? There’s no slack in the system to fall back on. This is one of the reasons why large chains ran out of toilet paper so quickly, but your local mom and pop sometimes had full shelves. A Megamart is designed to never have an extra pallet of anything lying around.

Yeah, but why now?

The coronavirus managed to completely ruin most of 2020, so why did we start seeing chip shortages in 2021, (and even more of them now in 2022,) an objectively better year? The short answer is that it takes a long time for chips to move from a factory in China to the places where electronics are made. The global supply chain involves long lead times. In 2020, we used up all of the chips that were already in the pipeline, and now the system needs to catch up. The slightly less short answer is that some industries fared better than others during the pandemic. AV uses many of the same microchips as the broader technology industry. When you put Wi-Fi connectivity in just about everything, you’re going to be competing for the relevant microchips with everyone else who does the same. The broader IT industry is also struggling to source its chips, and AV is competing against enormous global manufacturers for many of the same components. The largest manufacturers in our industry are putting in orders that are basically rounding errors compared to the orders coming in from IT and automakers. The overall demand for chips went up 17% between 2019 and 2021, with no extra supply to meet that demand. There literally aren’t enough of them to go around. And, once those chips are made, they still need to get from the factories where they’re produced to the factories where they’re put in finished products. Delays in shipping and trucking have further exacerbated the delays.

But I thought [Product X] was made in America? What gives?!

I’ll let you in on a little secret. Made in America often means “assembled in America from parts produced overseas.” Microchip manufacturing requires specialized equipment, ultra-clean rooms, and a skilled workforce to run it all. For most manufacturers, it’s far more cost-effective to source parts from elsewhere. Companies like Intel make chips here in America, but its market share had previously been on the decline.

We learned to bake sourdough. Surely we can make our own chips!

Please see the above and the article here by Sara Abrons about the inherent difficulties in manufacturing microchips. There is a growing movement to bring some of that production back here to the U.S. This could help with future shortages, but won’t help us with our current problems. And it will likely require a large investment in infrastructure. Companies like Texas Instruments and Samsung have announced plans to open new plants in America, but these new facilities cost billions of dollars to build and aren’t exactly quick to spin up. Then, you need to find employees who are skilled enough to run your factory but who are willing to work under difficult conditions (it’s not exactly a walk in the park to suit up in the clean suits that workers must wear to ensure that no impurities can get into the manufacturing process). Most Americans are (understandably) not willing to work the long hours put in by their counterparts at chip plants overseas.

When will this all end? Make it stop!

Buckle up, buttercups, because the shortage is projected to last well into 2022.

This is going to cost me, isn’t it?

Yup.

The entire technology market is seeing prices go up. Companies have announced higher shipping fees to help defray expenses. The prices of consumer electronics are on the rise as well. Purchasing a consumer-grade display to value engineer a job might not be an option for quite some time. And rush shipping charges have gone way up. Need that laptop battery this week? Expect to pay handsomely for it.

AV manufacturers are starting to raise prices and announce long lead times. This is likely to hit smaller integrators and those who don’t have cash reserves hard. You can’t sell systems if you don’t have the necessary hardware for them. Price increases are going to put a bigger squeeze on margins that were already getting tighter. For years, industry analysts have said that the days of companies making bank selling boxes are ending. This is only going to accelerate that process. That recurring revenue from service contracts is starting to look pretty helpful right about now.

How else could the global supply chain create chaos?

As I said earlier, the “just in time” nature of our global economy is exacerbating our supply chain woes. Efficiency is good for a bottom line, but it leaves no slack in the system to absorb disruptions. We’re also seeing bottlenecks at ports of entry (you can’t get your products if they’re stuck in shipping containers) and with trucking (we’re facing a nationwide driver shortage). I suppose the good news is that there might not be that many more places where the supply chain could break down? I apologize. I’ve probably kicked off some sort of nationwide warehouse problem with my attempt at optimism.

And, finally, let’s not be glib in acknowledging that the global pandemic has killed more than 5 million people. And that, sadly, that number will only continue to rise. Many of the people who died from COVID were the very people who produced and transported the goods that our industry sells. You can’t perform factory work from home. Or box things up in a warehouse from home. Or unload shipping containers from home. Or long-haul truck things from home.

In the aftermath of global shortages, factories will be built and back-orders will be filled. But if we want the system to truly recover, we all need to do our part to end this pandemic once and for all.